In the Victorian era, people would wash off with a sponge soaked in cool water and vinegar, use sweat-absorbing pads in armpit areas and overwhelm unpleasant smells with perfume. The most popular scent was ambergris known for its marine, sweat and earthy scent with a fecal note (if not properly aged). Since energy was obtained from burning of fuels, large amounts of sulfur were always present in the air, covering odors of animal and human waste released into river and streams.

Engineers eventually designed centralized closed water sewage treatment systems and modern plumbing, enabling rigorous personal hygiene. But in the early 1900s, fear-based marketing convinced people that

they smelled bad, and this turned niche deodorant trades into a $22 billion industry. Odorono (from "Odor? Oh No!") was one of the first antiperspirants at the forefront of this transformation.

The use of antiperspirant deodorants has been declining in recent years due to their potential effect on health and environment, and the availability of more natural and organic alternatives. COVID-19 pandemics has also negatively affected the deodorant market. As a result, the demand for deodorization has decreased during these times. But innovation continues.

Across North America, the deodorants market witnessed growth of few brands creating antiperspirants intended for alternative body parts, such as hands, face, and feet. For example, Gamer Grip Hand Antiperspirant, designed for athletes to improve their grip, has a lasting fragrance for 4 to 6 hours. Neat 3B Face Saver is an antiperspirant gel for the face that can be applied before makeup. Carpe No-Sweat Face is a natural, sweat absorbing gelled lotion created with sweat absorbing ingredients like jojoba esters, vitamin B3, silica microspheres, aloe vera, and colloidal oatmeal.

In the early 2000s, new types of deodorants appeared on the market.

Deo Perfume Candy, Swallowable Parfum, and Otoko Kaoru were designed as edibles, and the fragrance was supposed to be released from the user's mouth and nose. However, these products were eventually discontinued due to safety concerns, as well as their lack of popularity.

Beginning in the mid-2000s, many clothing companies started incorporating silver nanoparticles into their products including nano-engineered anti-odor textiles. While the technology was initially developed for use in the medical industry (antimicrobial wound dressings), nano-porous materials in clothing presented another way to manage body odor. These materials offered the potential to make traditional deodorants old-fashioned or even obsolete.

Ag nanoparticles, for example, are effective at slowing the growth of bacteria that cause body odor and itchiness. Nano-silver socks help in preventing bacterial and fungal growth. Haojey creates textiles comprising a TiO2 particle core to provide UV resistance, silver nanoparticles for antibacterial textiles, and nanobamboo for odor adsorption. Cotton

treated with pomegranate and galnut extract showed excellent deodorizing performance against trimethylamine. Odor-free medical masks are fabricated using Polyvinyl Butyral and Eucalyptus Anti Odor Agent. Aloe Vera and Polyvinyl Alcohol (AV/PVA) electrospun nanofibers show excellent results suppressing growth of S. aureus bacteria (by ~25%) although not E. coli. A team from UC Berkeley introduced a way to reduce underarm sweating and odor by using a cross-linked microporous copolymer containing methacrylate and acrylate units.

Unfortunately, many of nano-infused textile products are investigated as skin irritants. Besides, considerable amounts of Ag nanoparticles were found to be released on washing Ag nanoparticle integrated fabrics, which is highly toxic to aquatic life.

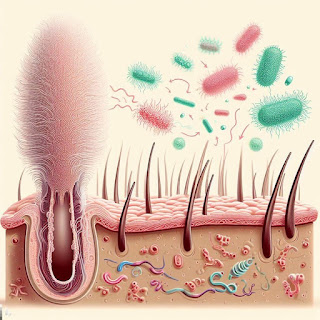

Another trend in the world of skincare that started in the late 2000s was topically applied probiotics.

Although the idea is not new, as research into the human microbiome began to uncover the role that probiotics could play in improving health, the use of probiotics, prebiotics and postbiotics to help combat odor-causing bacteria began to gain traction. Oral deodorizers with probiotics are already commonly found in the market in the form of chewing tablets, lozenges, and capsules. Topical probiotic formulations could exert anti-inflammatory effects by stimulating regulatory T-cells and release of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, within the immune system, competing with odor-causing microbes for nutrients, and aggregating and displacing them. When applied to the skin, Lactobacilli, for example, exhibits antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Cutibacterium (formerly Propionibacterium) acnes.

Topical microbiome transplantation (Roseomonas mucosa lysate cultured from healthy volunteers) is believed to improve atopic dermatitis by restoring

epithelial barrier function and innate/adaptive immune balance as well as via inhibition of S. aureus growth. Nitrosomonas eutropha improves appearance of skin. Transplantation of microbiome enriched in S. epidermidis helped to

reduce axillary malodor in siblings or other matching individuals. Bacteria responsible for odor emitted from the skin is known and is common for individuals suffering from a variety of odor disorders, including those with genetic variations in ABCC11, FMO3 and those with

idiopathic malodor. The presence of these bacteria in the gut microbiome

correlates with the intensity of malodor. Balancing composition of gut microbes will definitely help to improve the odor but may take a long time and

require tailor-made diets. And it is not clear if "suicide substrate inhibitors" such as iodomethylcholine are sufficiently safe to use.

More than a dozen topical probiotic species have been found to have a unique spectrum of characteristics, including

keratin adhesion, inhibitory action, organic acid

production, and inhibition of biofilm formation, skin whitening, moisturizing, anti-aging, anti-wrinkle and removing body odor. A new bilayer vaginal tablet of Lactococcus lactis has been designed for the treatment of vaginal bacterial infections and could also help to combat unpleasant odors. And so could Nitrosomonas eutropha, although so far it was only proven to help with acne. Genetically modified bacteria are also being investigated as topical therapeutics. Candidate genes are Fillaggrin, LEKTI, IL-10, genes encoding growth factors and hormones. Studies of safety and efficiency are still, however, in very early stages. The application of high amounts of bacteria, could, for example, lead to a skin immune reaction with irritation and side effects as a result. It could also lead to infection.

The skin microbiome is relatively stable and

quickly restores after washing and skincare product application, even if they contain antimicrobials. The reason is, skin microbiome is actually derived from within the skin, the deeper stratum corneum layers, skin hair follicles and is connected to the

gut microbiome. Skin microbiome transplantation methods are currently being investigated and showed some promising results although many challenges remain that need to be overcome.

Probiotic-infused products and skin transplants are gaining popularity due to their ability to promote healthy bacteria growth on the skin, which can, for example, help reduce body odor. However, there is still a lack of strong scientific evidence of effectiveness and a lack of thorough understanding of side effects. Probiotics are living microorganisms, which means that they are sensitive to environmental conditions and can be difficult to work with. This can make it challenging to incorporate probiotics into skincare products in a way that preserves their effectiveness and stability.

Finally, there are regulatory issues to consider when it comes to introducing new probiotic-based skincare products to the market. In order to be sold as a cosmetic product, a skincare product must be safe and effective, and the manufacturer must provide evidence to support these claims. This process can be time-consuming and costly and may discourage some companies from investing in the development of new probiotic-based skincare products.

Overall, while there is a growing interest in the potential benefits of probiotics, prebiotics and postbiotics for the skin, the development of new probiotic-infused skincare products is likely to continue to be slow and incremental as researchers and manufacturers work to understand more about how probiotics work and how they can be effectively incorporated into skincare products.

It is likely that skincare products developed in the future

will be tailored to specific genetic profiles, as researchers continue to learn more about the role that genetics plays in skin health and the skincare concerns that people may have.

One example is a urea-containing moisturizer that could be effective for people with a certain genetic variation in the filaggrin gene, Transient erythema (reddening of skin) is a potential side effect. A number of genes (such as MC1R, ASIP and BNC2) are related to skin conditions including sun sensitivity, skin moisturizing function, oxidative stress, stretch marks, and skin inflammation and are being investigated in personalized skincare R&D.

Gene therapy and enzyme replacement therapies have achieved some notable successes in recent years. For instance, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Luxturna for a rare form of inherited blindness, and Kymriah using genetically modified T cells to attack cancer cells, in 2017. However, the costs of research and development and the risk of side effects are extremely high.

As a result, it can be difficult to obtain funding for non-fatal conditions like TMAU (trimethylaminuria).

Trinzyme, a company focused on enzyme replacement therapies, was founded in 2011 with the goal of developing treatments for TMAU. While the company was able to secure initial funding, it has not yet been able to deliver on its promise of a treatment for this condition. Despite these challenges, the potential for gene therapy and enzyme replacement therapies to revolutionize the way we treat and prevent diseases remains significant, and research and development in these fields continues to advance.

In 2022, several companies started testing their deodorizing cosmetic products intended to block smelly chemical trimethylamine, emitted from the skin if the liver cannot completely break down this product of essential nutrients. Spain-based perfume manufacturer Eurofragance has recently teamed up with a Barcelona Children Hospital on a project to neutralize the strong odor of those who suffer from trimethylaminuria (caused by genetic mutations that affect the FMO3 function of the liver).

The hospital's program initially focused on pediatric subjects with primary carnitine deficiency, manifesting as metabolic encephalopathy, lipid storage myopathy, or cardiomyopathy. Since the patients are not able to process long-chain fatty acids to convert them into energy, the accumulation of toxic fatty acyl derivatives impedes gluconeogenesis and urea cycle function which, in turn, causes hypoketotic hypoglycemia, transaminase elevations, and hyperammonemia - hence fishy odor. Eurofragance solution has citrus notes blocking the fish odor receptors in the nose. This way the fishy odor does not disappear, but it is not perceived. Eurofragance designed body cream lotion with 1% fragrance, an eau de toilette with 5% fragrance and a body serum with 2% fragrance. Other businesses designing their own solutions were Nannic "Skin care by science", and stealth-mode teams from British and US companies.

While there is still a lot more research to be done, the development of these new deodorizing cosmetic products has provided hope for those who struggle with trimethylaminuria and similar conditions.

REFERENCES

Callewaert C, Knödlseder N, Karoglan A, Güell M, Paetzold B. Skin microbiome transplantation and manipulation: Current state of the art. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 2021 Jan 1;19:624-31.

Gabashvili IS. Cutaneous Bacteria in the Gut Microbiome as Biomarkers of Systemic Malodor and People Are Allergic to Me (PATM) Conditions: Insights From a Virtually Conducted Clinical Trial JMIR Dermatol 2020;3(1):e10508 URL: https://derma.jmir.org/2020/1/e10508 DOI: 10.2196/10508

Gabashvili IS. Identifying subtypes of a stigmatized medical condition. medRxiv. 2019 Jan 1:19005223.

Habeebuddin M, Karnati RK, Shiroorkar PN, Nagaraja S, Asdaq SM, Khalid Anwer M, Fattepur S. Topical Probiotics: More Than a Skin Deep. Pharmaceutics. 2022 Mar 3;14(3):557.

Lee GR, Maarouf M, Hendricks AJ, Lee DE, Shi VY. Topical probiotics: the unknowns behind their rising popularity. Dermatology Online Journal. 2019;25(5).

Lee YH, Lee SG, Hwang EK, Baek YM, Cho S, Kim JS, Kim HD. Deodorizing performance and antibacterial properties of fabric treated with pomegranate and gallnut extracts compared with properties of commercial deodorizing and antibacterial agents. Textile Science and Engineering. 2016;53(1):45-54.

Myles IA, Earland NJ, Anderson ED, Moore IN, Kieh MD, Williams KW, Saleem A, Fontecilla NM, Welch PA, Darnell DA, Barnhart LA. First-in-human topical microbiome transplantation with Roseomonas mucosa for atopic dermatitis. JCI insight. 2018 May 5;3(9).

Qadir MB, Jalalah M, Shoukat MU, Ahmad A, Khaliq Z, Nazir A, Anjum MN, Rahman A, Khan MQ, Tahir R, Faisal M. Nonwoven/Nanomembrane Composite Functional Sweat Pads. Membranes. 2022 Dec 5;12(12):1230.

Yang J. Personalized Skin Care Service Based on Genomics. InInternational Conference on Health Information Science 2021 Oct 25 (pp. 104-111). Springer, Cham.