Our previous trials showed that while there is no one-size-fits-all solution to MEBO and PATM symptoms, some metabolite measurements and self-reported data can distinguish different subtypes of these conditions with very high accuracy.

Hence, we may need different treatments for sufferers with different metabolism - for example, abilities to process sugar in their food or higher production of putrescine in urine (could it be due to pseudomonas and enterobacteria in the gut?).

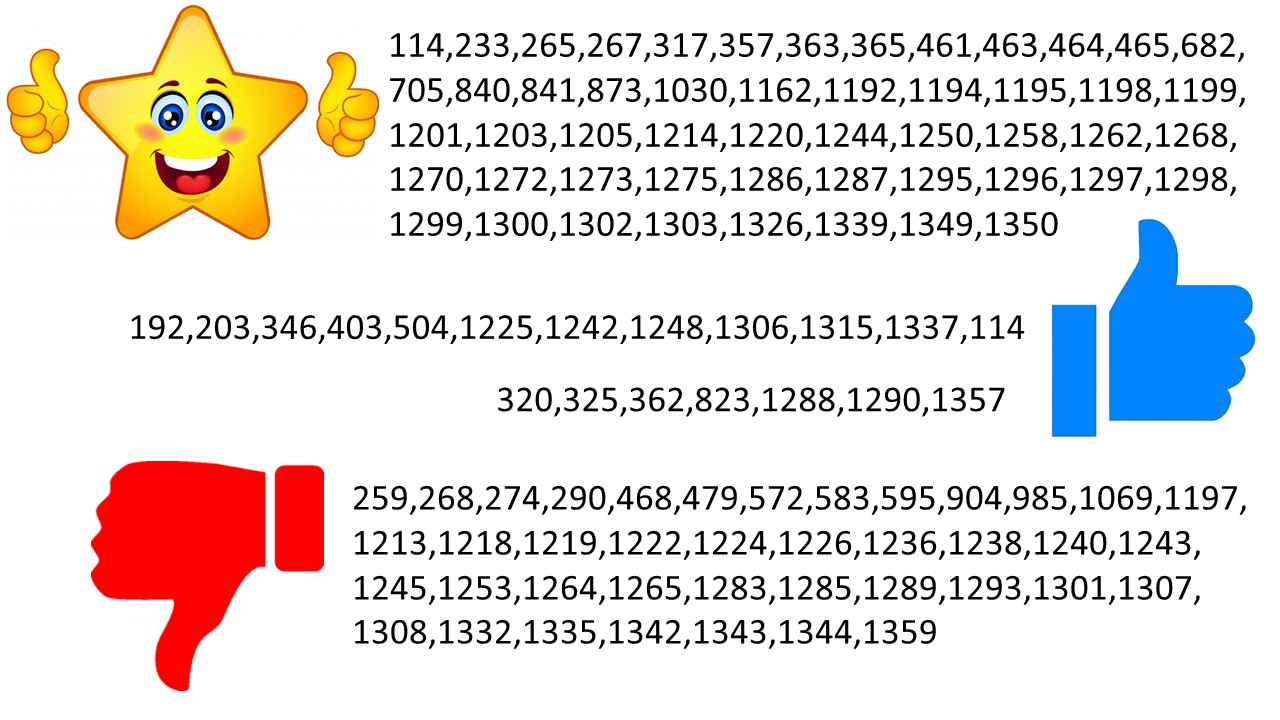

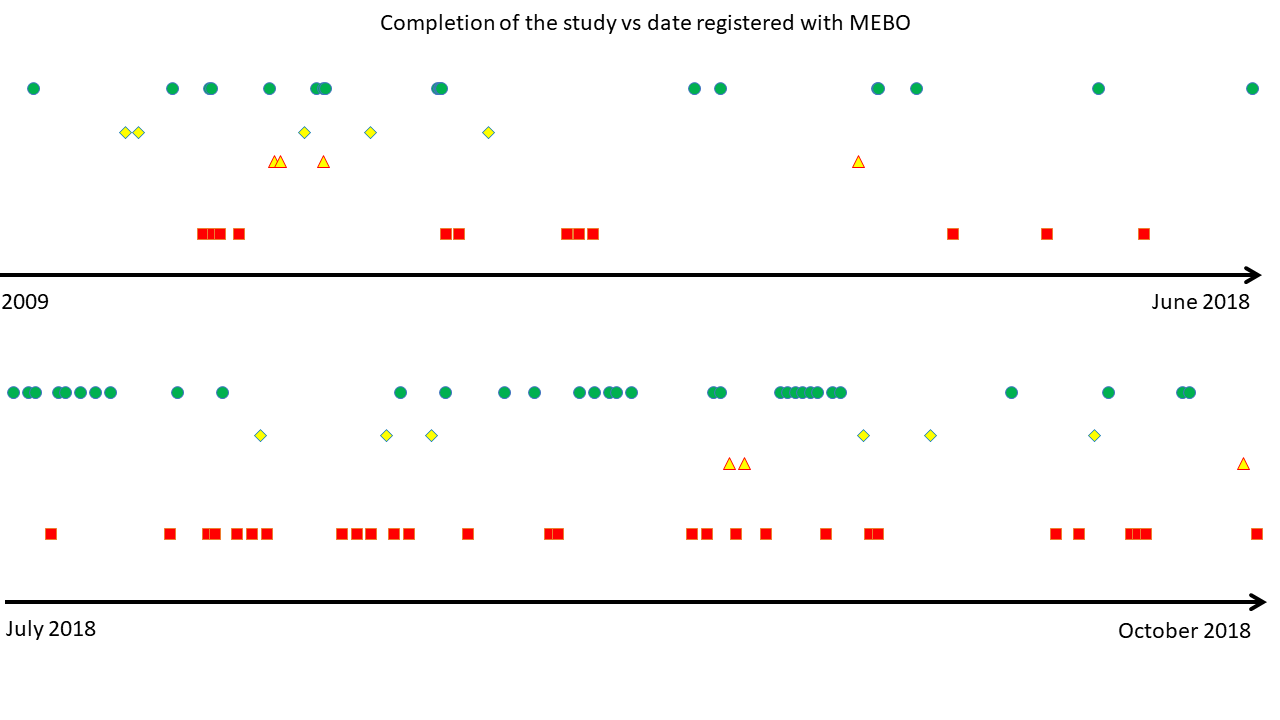

Our previous studies had much fewer variables differentiating MEBO subtypes and fewer participants (NCT02692495: 16 viable samples from 11 men and 5 women; NCT02683876: 15 viable samples from 10 women and 5 men). We are now collecting the biggest ever MEBO dataset for the current study, NCT03582826, with about 5 times larger number of participants than previous studies. One of the questions asked in QoL survey was whether participant's condition was

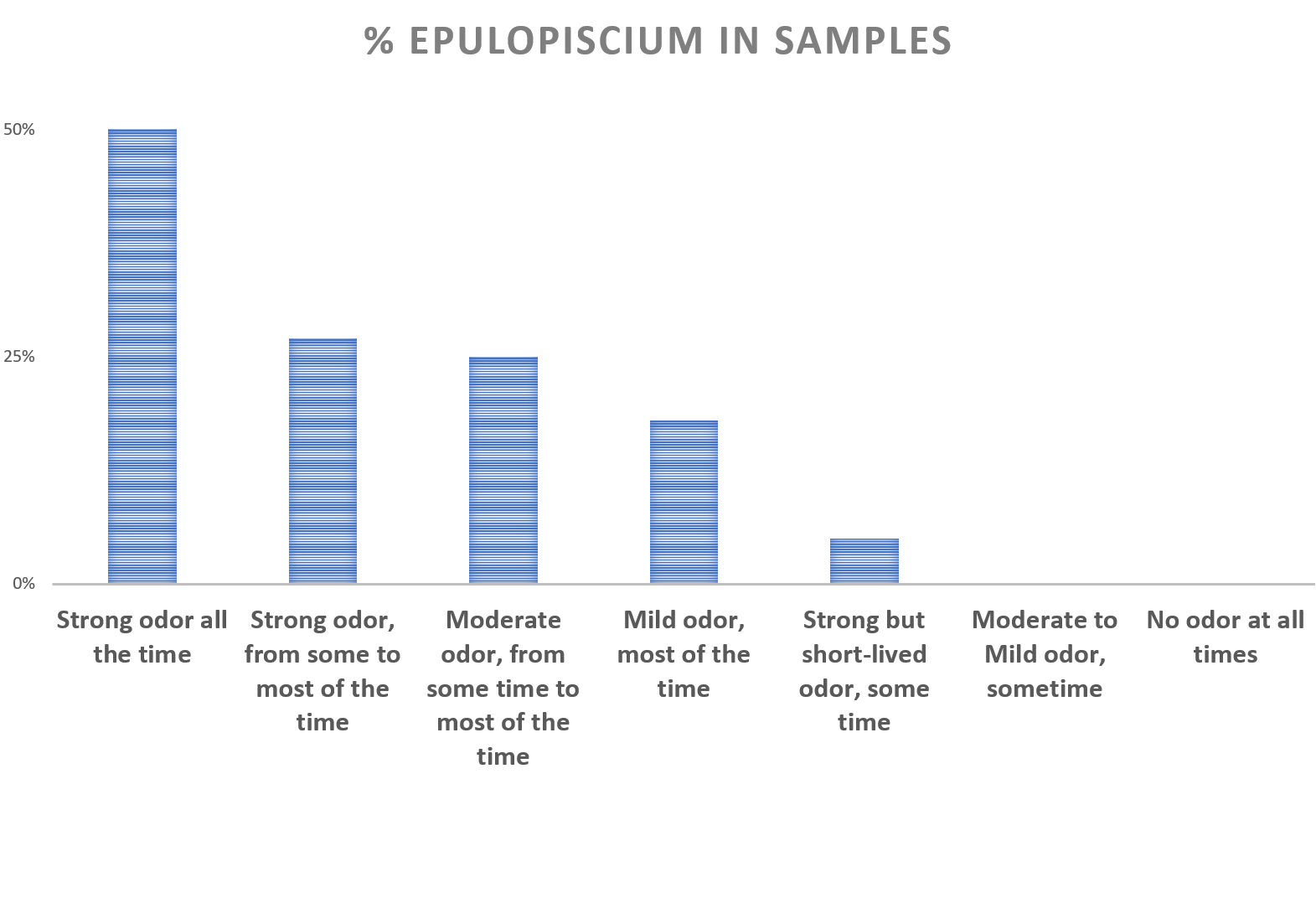

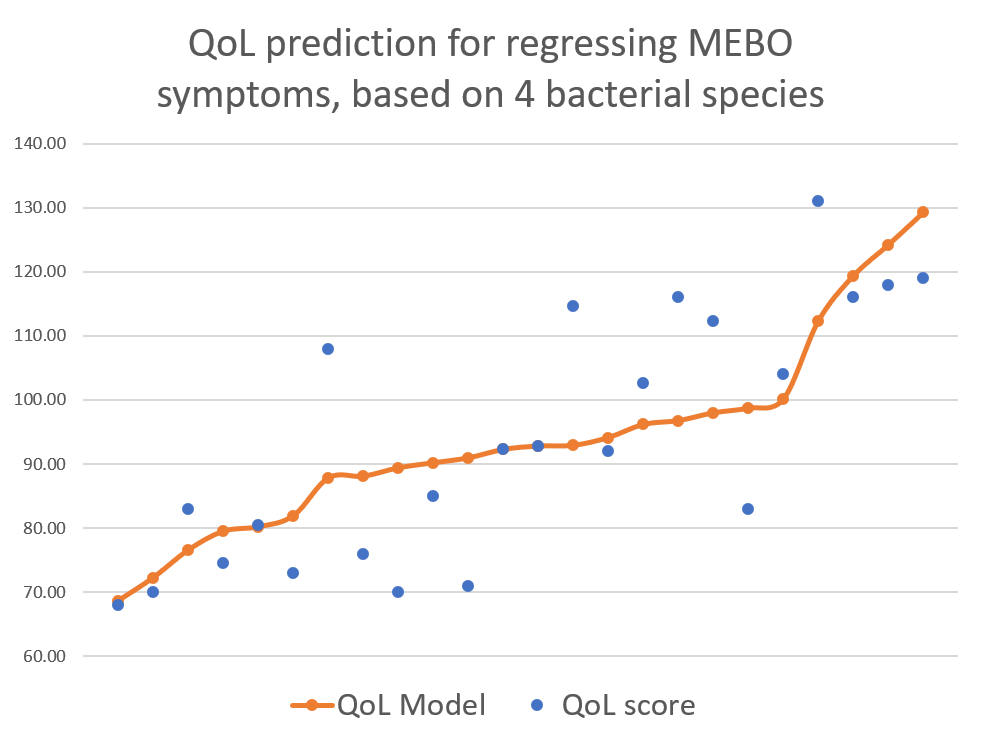

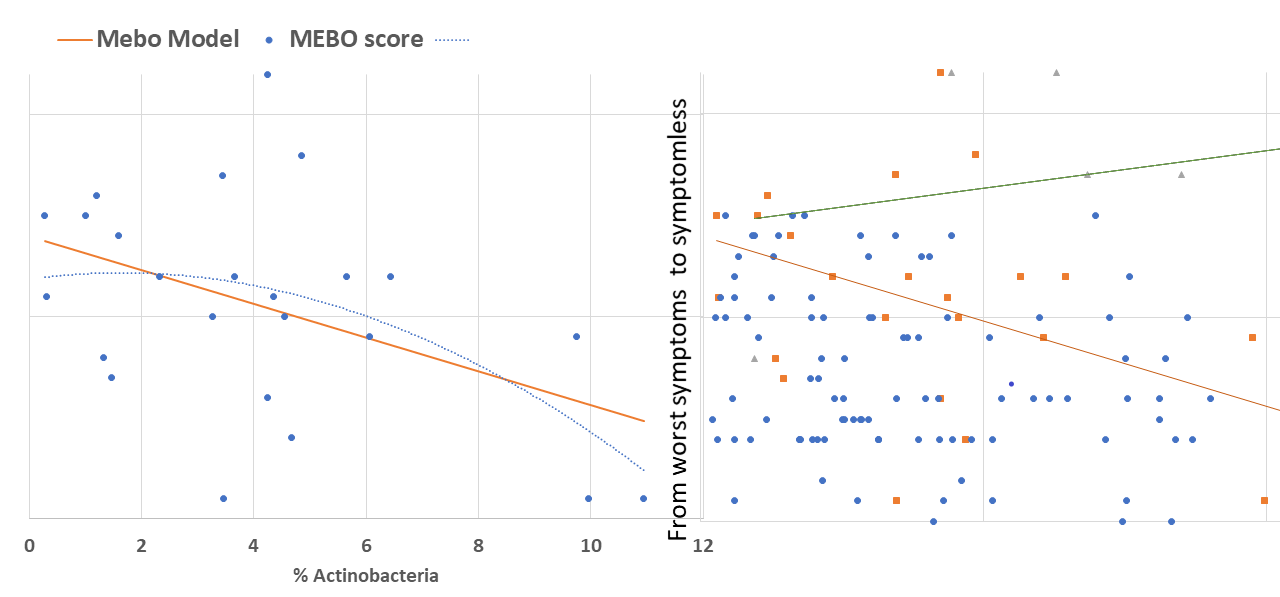

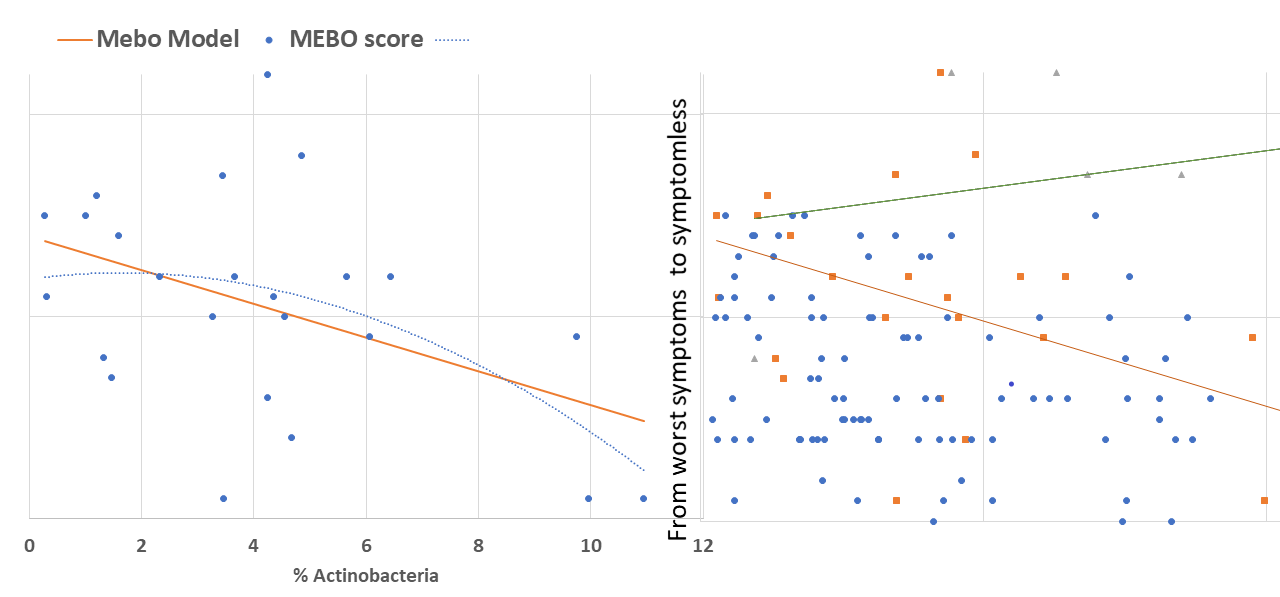

active/progressing, regressing or they were in remission. We decided to start our exploratory analysis from the subset of sufferers with "disappearing" symptoms - when participants felt they were on the road to improvement. The figure above shows a quick-and-dirty model describing how compositions of just 4 microbes could predict quality of life for these participants. Interestingly, these bacteria did not seem to be responsible for their MEBO or PATM symptoms, only overall wellbeing. The figure on the left shows how just one class of bacteria - Actinobacteria - correlates with the severity of MEBO symptoms in those whose condition is improving. It's very noisy, but it seems that increasing numbers of this bacteria (responsible for the pleasant smell of rain) helps to improve odor. Yet, look what happens when we throw in data from those with active disease or in remission (right section of the figure above) - the pattern is completely lost. Even more so, looks that those who already achieved remission care less about this bacterium and sometimes even slightly benefit (at least, in their own opinion) if they slightly reduce its population. Obviously, we need to subdivide the data better before attempting to build predictive models and look at a lower level of microbial hierarchy.

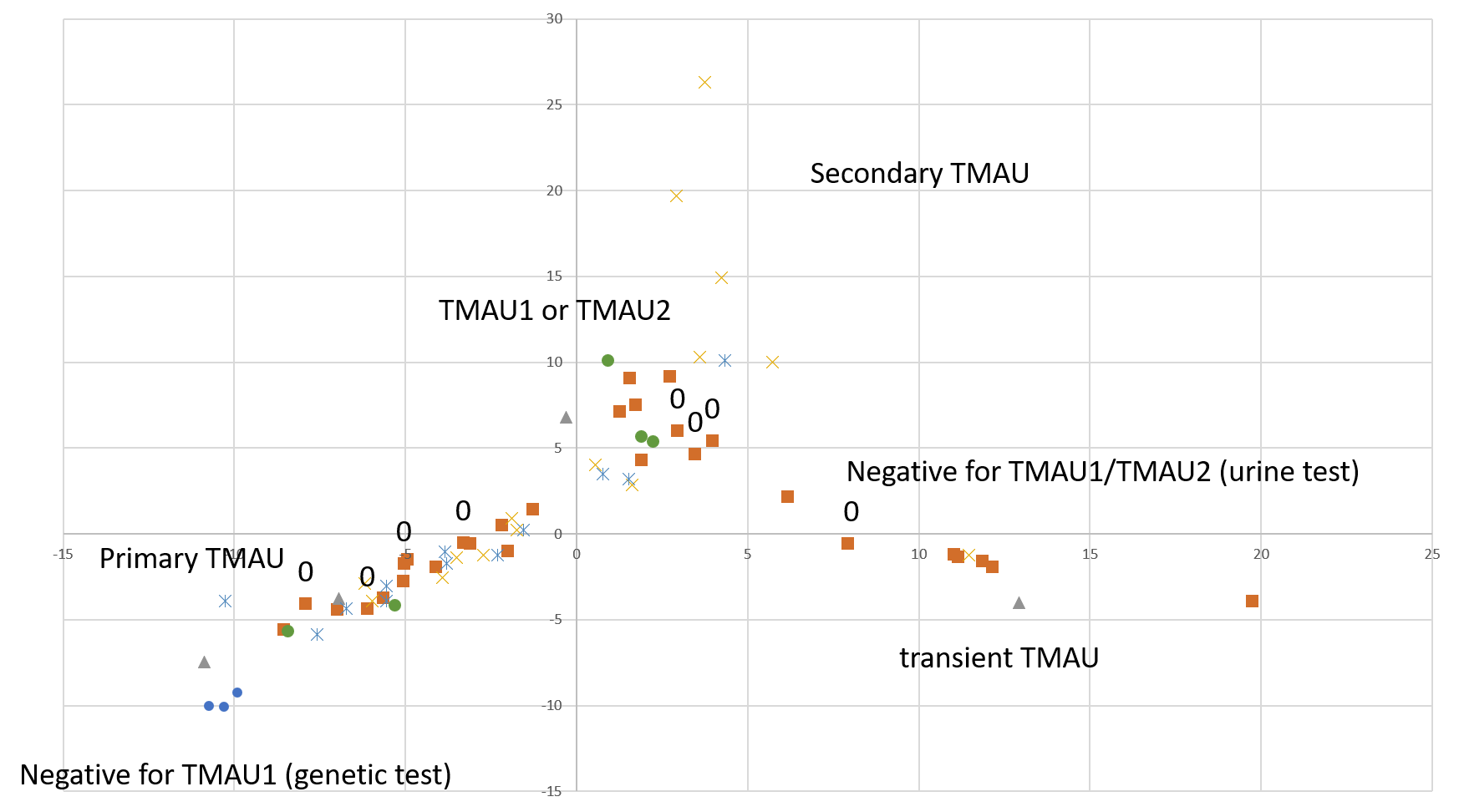

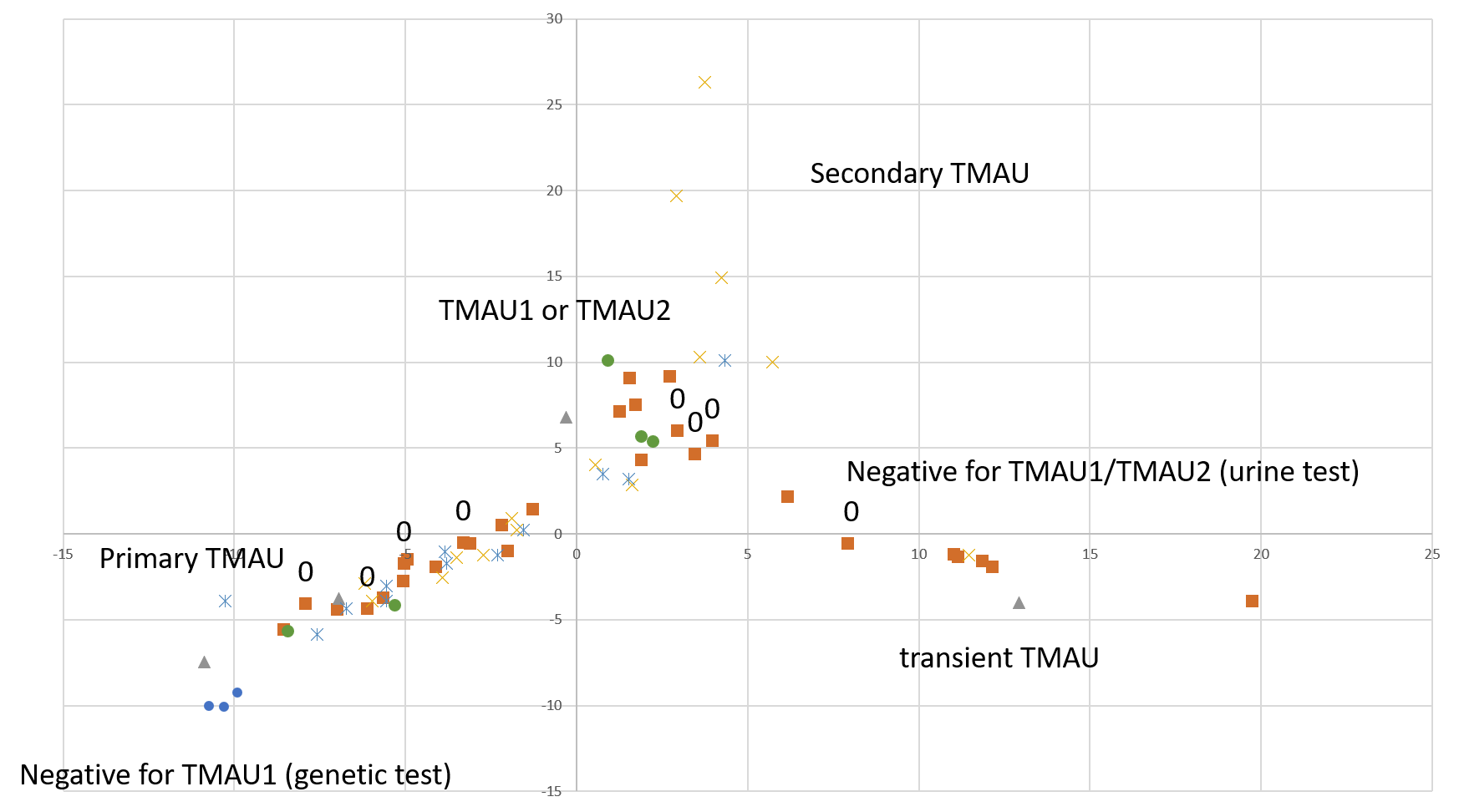

A quick-and-dirty principal component analysis of available samples vs all microbial species (figure on the right) shows that our research participants that tested negative for TMAU have different microbial profiles than those who tested positive, and microbiome for TMAU1 is different from TMAU2.

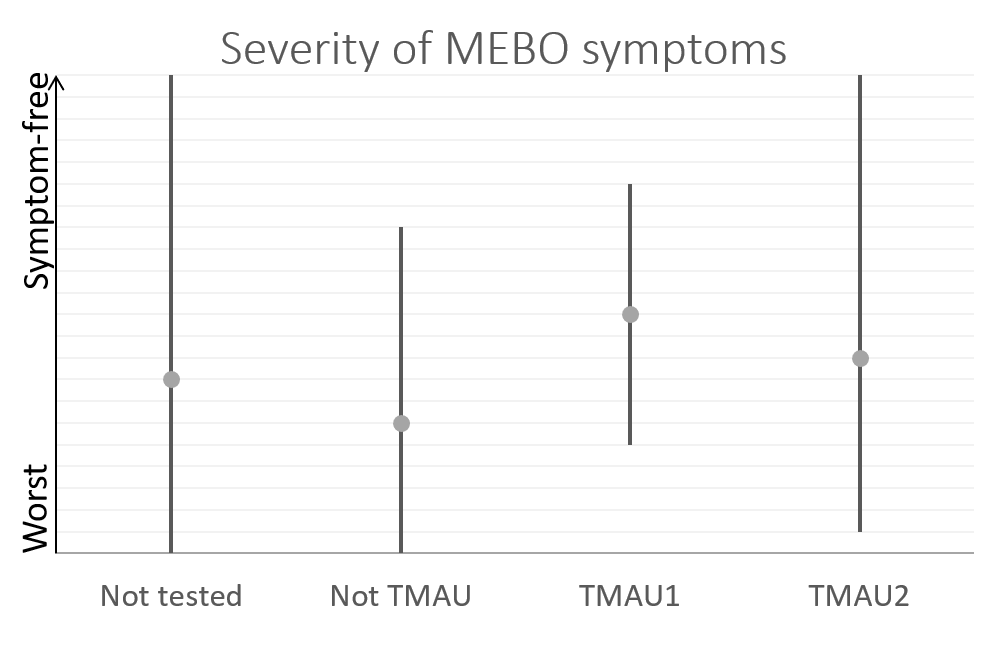

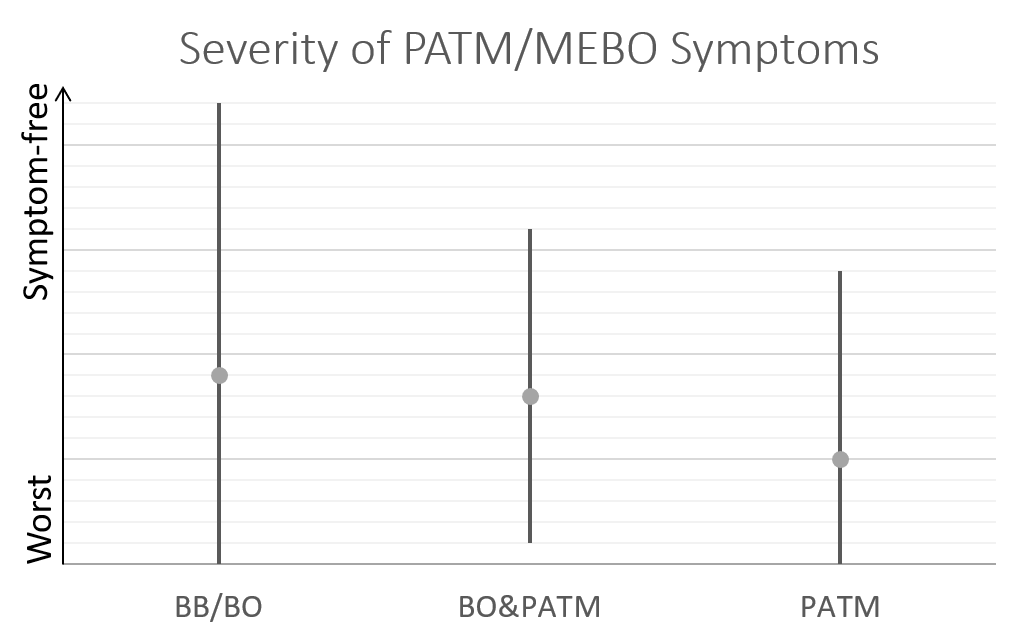

So far, we have over 40 samples of those negative to TMAU1 and TMAU2, and over 30 samples of those diagnosed as either TMAU1 or TMAU2, dozens of samples of those with PATM with or without body odor or bad breath. Interestingly these groups significantly differ in the self-perceived severity of their symptoms.

Average MEBO score is the worst for those diagnosed negative to TMAU. (The figures show average MEBO scores along with their variations) Surprisingly, it's the best for those diagnosed with the most severe form of TMAU - TMAU1! This shows that it's possible to learn to control symptoms even in extreme cases.

PATM symptom severity is even lower than MEBO symptoms for TMAU-negative individuals.